The Gut Crunch of Islamic Feminism

An explanation of a movement that has been hiding under the veil, and is growing in the eyes of feminists around the world

Where it all began

Feminism has been the main topic for countless news articles, as the trending hashtags for almost every social media post. It also has been the controversial conversation since the MeToo campaign. The rise of women empowerment has been increasing over the last few years, and according to many sociologists, 2018 is “the year of women”. However, there are many different layers of feminism that sometimes are forgotten. There are women who are fighting different battles in countless societies around the world, and their stories and their struggles are just as important and relevant as the ones that are being televised and written. One of those layers of feminism is Islamic feminism.

The term ‘Islamic feminism’ is defined by historian of women and gender issues in Muslim societies, Margot Badran, as “a feminist debate and practice expressive within an Islamic example.” Islamic feminist ground their arguments in Islam and its teachings, as well as seek the full equality of women and men in the personal and public sphere. This includes non-Muslims in the debate.

Islamic feminism is defined by Muslim women as the role that is mainstream as a sexual feminist initiative. It has been anchored within the debate of Islam with the Qur’an (the central religious text of Islam, which Muslims believe to be a revelation from God) as its central text, according to Moroccan sociologist Leila Ahmed and African American sociologist Amina Wadud.

In the United States, before the 9/11 attack, Muslim feminism was on a rise. Women were wearing their head scarfs around their faces with pride (clothing that a lot of Muslim women wear in modesty, or for their devotion to God). They work as not only symbol of their religious identities, but a medium through which they navigate their religious commitments in contemporary socio-political climates, (re)defining a form of women's agency traditionally excluded in feminist discourses. This changed after 9/11. After the attacks from al Qaeda, the Arab community had a target on its back. The same women who were welcoming their veils as an empowerment cloth that embraced their freedom, it became more of a symbol to Americans as the country that destroyed another.

Susan M Akram, an associate professor of Law at Boston University School of Law wrote a book about the aftermath of 9/11, or what is known as the “War on Terror” epidemic. In it, she states: “For months following the attack, Muslim women were forced to hide in their homes to avoid harassment and violence and those that chose, or had to, go into public would wear their scarves in a manner that could not be recognised as being affiliated with their religious beliefs. Furthermore, when responses from the Islamic community were given concerning the devastating events, the women of Islam were silenced.”

“For months following the attack, Muslim women were forced to hide in their homes to avoid harassment and violence and those that chose, or had to, go into public would wear their scarves in a manner that could not be recognized as

being affiliated with their religious beliefs. Furthermore, when responses from the Islamic community were given concerning the devastating events, the women of Islam were silenced.”

-Susan M Akram

Feminism in the 21st century

After the War on Terror epidemic, more women have spoken about the feminist movement in their culture. Ghaliya Djelloul, a writer for Eurozine, says about Islamic feminists: “Positioning themselves as a marginalized social group, Islamic feminists claim their right to choose their identity rather than suffering it, and to maintain a multiple self-awareness both as women and as Muslim women facing a variety of forms of oppression.”

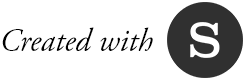

More women of the Islamic faith are trying to figure out what “feminist muslim” looks like and how to fit in their lifestyle, clothing, and way of living. A lot of women have conflicting opinions of wearing their hija, which is a head scarf that most Muslim wear in the presence of men. Sidra Binte , a contributing writer for the Huffington Post who is Muslim, says about the hijab is “The freedom to practice one’s religion, symbolic of our obedience to Allah (or God). It means modesty, it is an outer manifestation to our inner modesty. There’s a very common misconception about the hijab that it has only been imposed on women when in reality, men too have been asked to lower their gaze, grow a beard and to guard their modesty.”

Today, women are living in a society where they are subjected to sexualization and objectification-this is where the hijab de-sexualises women. It gives them recognition for who they are and not for what they look like. Today, women are subjected to inferiority complexes because of what they look like or if they don’t meet the standards set by patriarchal society. This is proven in countless makeup industries, where they advocate to most women that to be more confident and to be liked by men, they have to be fair skinned and slim. Wendy Shalit, the writer of “A Return of Modesty, Discovering the Lost Virtue” writes: “Hijab is a symbol of empowerment and feminism wherein the woman not only accords herself self-respect but also demands it from others.”

Organisations started forming where Muslim women can be a part of a community and/or group where they do not feel lonely or isolated from the world. Groups like SIS support women in this type of predicament.

Sisters in Islam (SIS) is a Malay organisation that fights for the rights of women within the frameworks of Islam and universal human rights. It started with the simple question: “If God is just as Islam is just “why do laws and policies made in the name of Islam create injustice?”. SIS work focuses on challenging laws and policies made in the name of Islam that discriminate against women. Their mission is to promote the principles of gender equality, justice, freedom, and dignity of Islam and empower women to be advocates for change. They seek to promote a framework of women's rights in Islam which take into consideration women's experiences and realities; they want to eliminate the injustice and discrimination that women may face by changing mindsets that may hold women to be inferior to men. They want to increase the public knowledge and reform laws and policies within the framework of justice and equality in Islam.

Having groups like this for Muslim women allow them to have a voice, and to fight together on some of the issues that impact their culture, and around the world. It gives them a safe haven to express themselves around women who are like minded, and to be able to have a force to fight for their rights.

The Future

For the future, it would be to stop using the term “Islamic feminism”. Rachelle Fawcett; a Muslim journalist living in Afghanistan, is quoted saying about the future of Islamic feminism, “We do not need a new word to replace ‘feminism’ to avoid the automatic gut-crunch that comes from the popular stereotypes, as it would be equally unjust to demand a new word for “Muslim”, but rather to allow ourselves to gain more open and well-rounded understanding of what Islamic feminism is.”

Islamic feminism is an evolution that goes against tradition in the eyes of some men who have created the rules of society today. However, in the future, there can be equality that includes not only women, but all human beings who are left out of traditional Islamic views.

Time and changing socio-political contexts will continue to change definitions and agendas associated with Islamic feminism. Though it might not be a singularly defined movement, it calls for the centring of Muslim women's voices and humanity for traditionally marginalised groups within mainstream society and Islamic traditions.