The Land of Song: The great Welsh Male Voice Choir

Culturally identifying as Welsh is a somewhat difficult task. After singing with Dunvant Male Voice Choir, Alex Myles may have found the solution

“There are fears that Welshness might not last. We worry about it more than others do. We beat ourselves up about these kinds of things too much,” says Professor Martin Johnes, Welsh historian and author of Wales: England’s Colony? He regards our relationship to England as fundamental to how we think about ourselves, in terms of society, economics, politics and culture.

These fears may be a reason why the Welsh government are pushing for a million Welsh speakers by the year 2050. In terms of culture, the Welsh language is an important means in setting ourselves apart as a distinct nation, yet only 18% of us can speak it fluently, let alone actually use it in a day-to-day context. Many identify as Welsh without speaking the language, including myself, so how can non-Welsh speakers culturally exercise their Welshness?

Sport helps us get behind our nation with no real socio-political context, we are undoubtedly a nation of rugby lovers and recent success has seen a peaked interest in Welsh football. But the rich singing tradition of Wales is often neglected in this regard.

Images courtesy of Dunvant Male Voice Choir

Images courtesy of Dunvant Male Voice Choir

Images courtesy of Dunvant Male Voice Choir

Images courtesy of Dunvant Male Voice Choir

Images courtesy of Dunvant Male Voice Choir

Images courtesy of Dunvant Male Voice Choir

Images courtesy of Dunvant Male Voice Choir

Images courtesy of Dunvant Male Voice Choir

Images courtesy of Dunvant Male Voice Choir

Images courtesy of Dunvant Male Voice Choir

Singing, synonymous with rugby, is a cornerstone of Welsh culture. Wales is often referred to as the land of song, due in part to its saturation of male voice choirs which have their roots in the chapels that sprung up in eighteenth century. These chapels accommodated for the new influx of migrants into Wales, enticed by the booming iron and coal industries. By the nineteenth century, singing became an inherently nationalistic activity; this was a time where users of the Welsh language were depleting fast, miners and unions were striking, and schools were becoming increasingly Anglicised.

To this day, choral activity has been proven to enhance singers’ national and cultural identity. With eight male voice choirs in my hometown of Swansea alone, I therefore ask a friend and old music teacher of mine if I can attend a choir rehearsal in order to feel more assured in culturally identifying as Welsh, after finding the Welsh language difficult to learn by myself and becoming fed up of Cardiff match days.

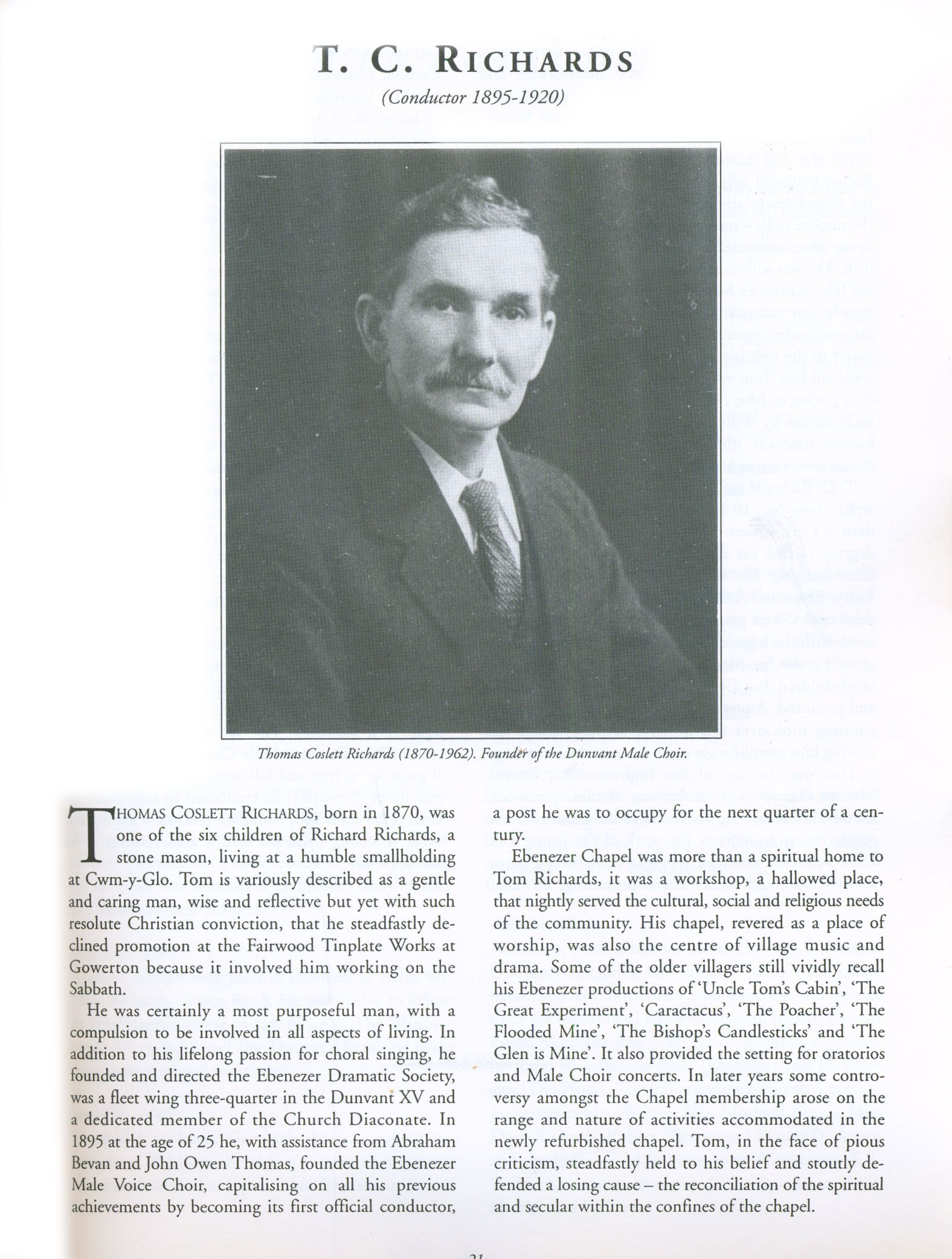

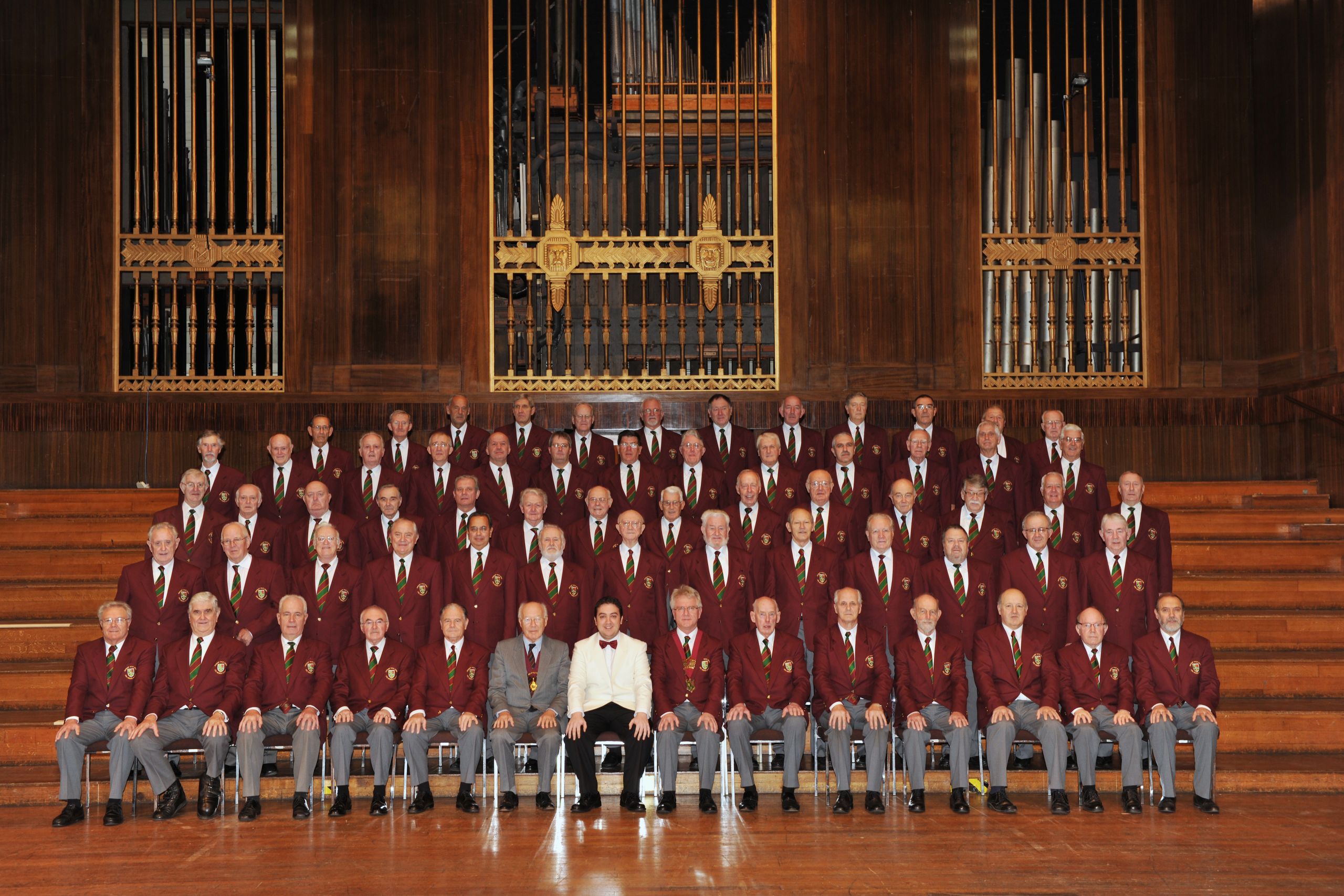

Jonathan Rogers, Jon, has been the conductor of Dunvant Male Voice Choir since 2007.

The choir itself was founded in 1895 by members of the Ebenezer Congregational Chapel who were miners, steelworkers and quarrymen. The choir still practice in this small suburban chapel, which Jon calls their spiritual home.

It’s also remarkable to think in their 125-year history, the choir has only had ten conductors. “When people come here, they stay for a while,” says Jon. “Welsh male singing is one of our (Wales’) only exports,” he continues, “so it’s something we’re quite proud of.”

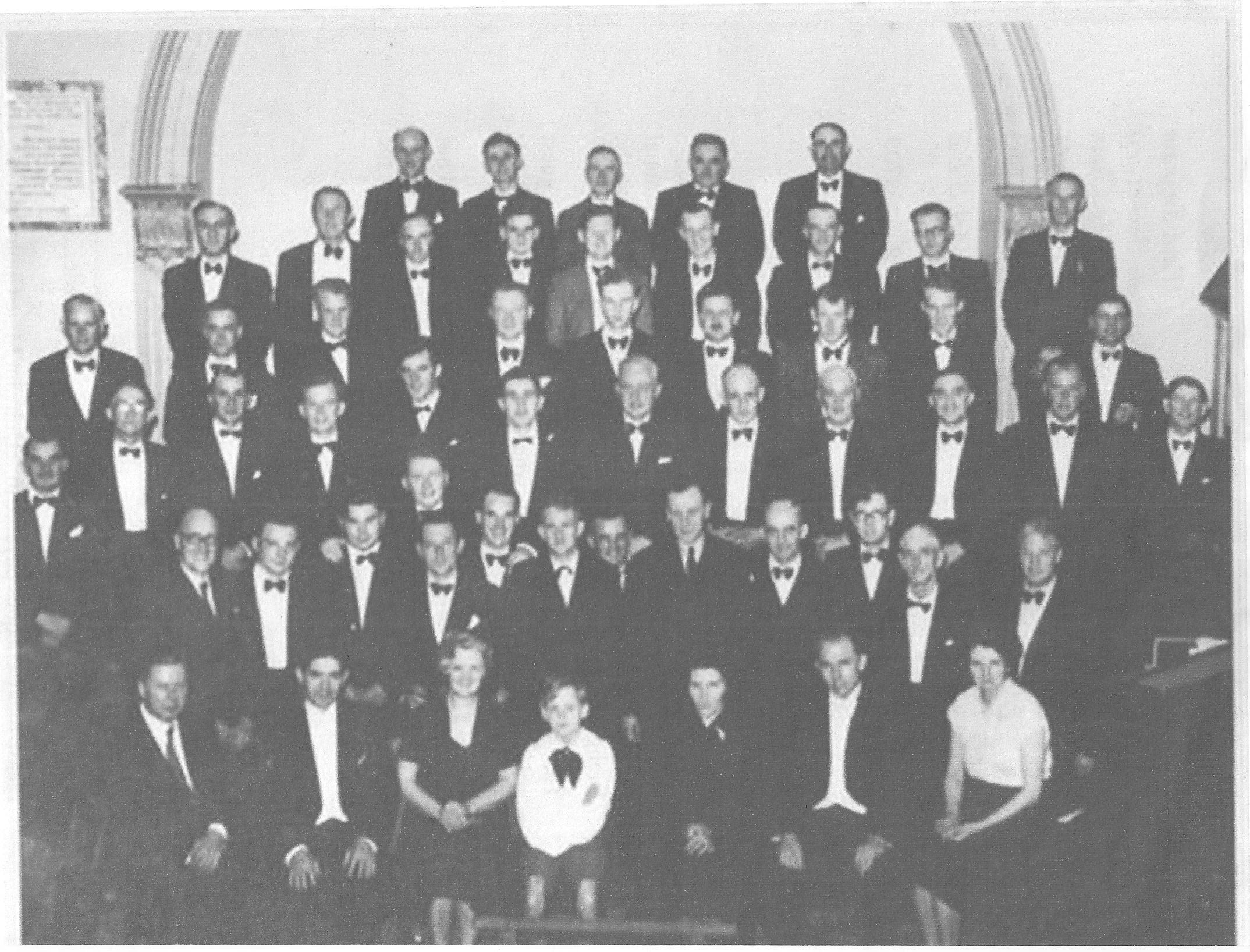

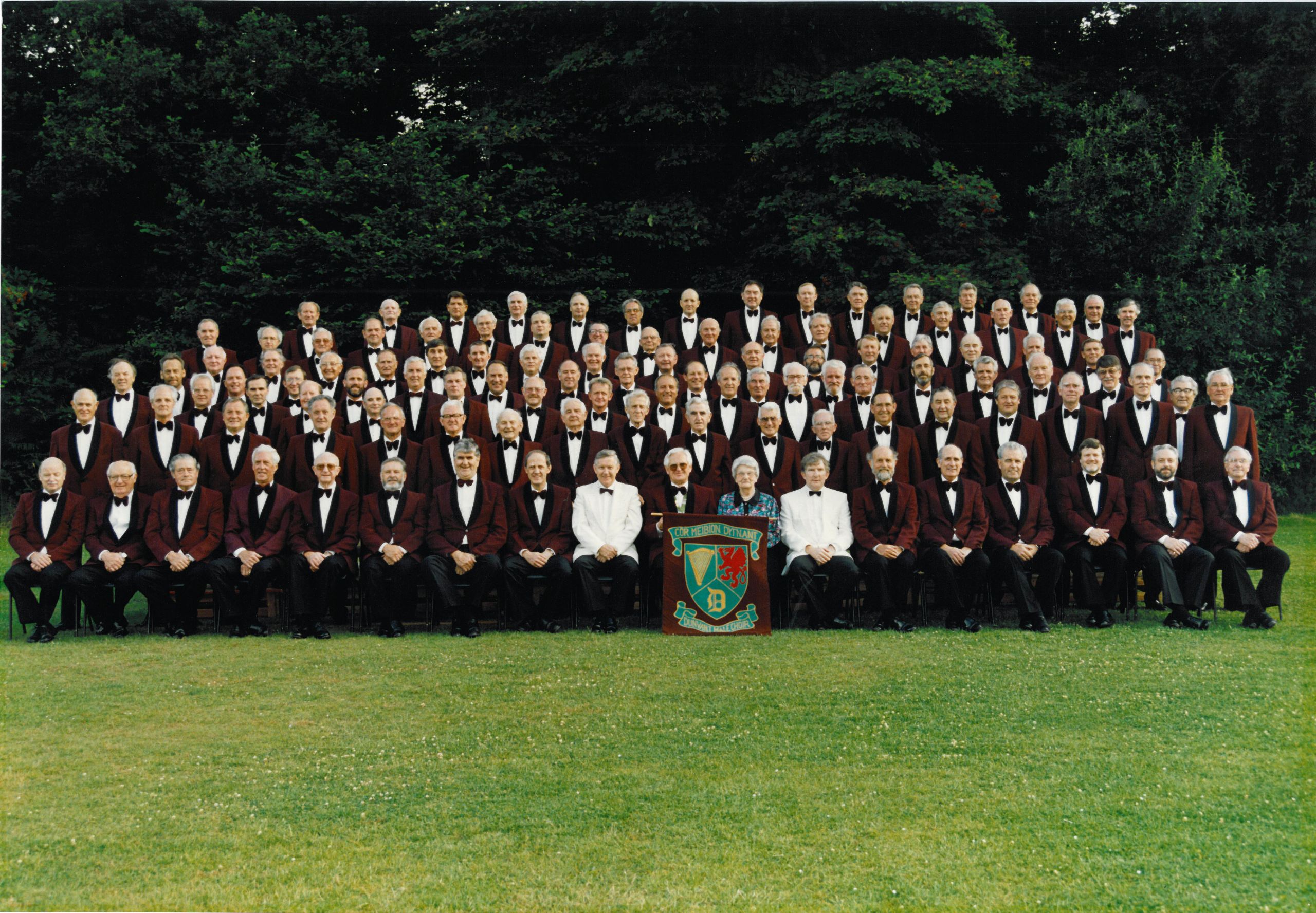

Dunvant Male Voice is the oldest choir in Wales with an unbroken history in that it didn’t stop singing during the World Wars. The choir has performed all over the world, from Singapore to the States, from Royal Albert Hall to Brangwyn Hall. Before we were all housebound, members were rehearsing for their landmark 125th anniversary concert in July, featuring Sir Bryn Terfel.

On arriving at the chapel on a chilly March evening, I was greeted to a sight of scalps and the sound of coughs and splutters. I started chatting to Glyndwr Prideaux and Alan Walters, the chairman and vice-chairman respectively. Glyn used to live next door to my grandparents and remembers my mum playing in the garden as a little one. It’s not really an exaggeration when people say everybody in Wales knows each other, especially in Swansea.

Bringing the rehearsal to a start, Jon stands atop his podium and introduces me to the gents. I’m met with applause so it’s clear these old boys love the camera.

Welsh choirs are now no longer confined by traditional hymns, the first song on the running order is Anthem from the musical Chess. There are also other musical theatre favourites, like Pure Imagination and I Dreamed a Dream.

Tentative at first, I eventually build enough courage to join in. Realising my lack of range, I sing along to the 'bass 2' part. The song is Arwelfa (Auditorium), composed by John Hughes, the brother of Arwel who composed another iconic Welsh hymn Cwm Rhondda i.e. Bread of Heaven. You know, the rugby one.

Another Welsh hymn follows – Pennant, using an original arrangement Jon made for the choir. He's keen to get the message of the words across to the non-Welsh speakers, the first line roughly translating to 'Here is love as vast as the ocean'.

The boys know this off-by-heart, so I look like a right numpty. Despite picking up the tune quite quickly, I get lost in the sheet music and the Welsh lyrics don't help. I'm singing the bass part again but stood among the tenors, who sing in a higher range. Although developing a receding hairline and beer belly of my own, I feel I stand out quite a bit here. Nonetheless, I’m stunned by the notes these gents can reach.

The last 'Amen' rings out, bringing the rehearsal to a close. Geoff Evans, affectionately known as Effie, asks me if I care to join him and the boys ‘for a sherry’ at the rugby club. I oblige.

Effie is the longest serving member of the choir, singing with Dunvant for 62 years. Over what could be his 62nd pint of bitter this week, he tells me “You’ve got to commit fully if you’re here, and I’m only 67 years old now.” Liar.

It was also a special occasion that evening, as Arnold Phillips – another long-serving member – celebrated his 82nd birthday. A 4-part harmony Happy Birthday (and its translation Penblwydd Hapus) rings out and the bottle of whisky that was put behind the bar was dished out accordingly, as was a jug of water for topping up.

After becoming acquainted with the boys and seeing their own choir vault at the club, overflowing with merchandise like magazines, CDs and posters, it soon became clear that this is more than just a sing on a Wednesday for these boys; it’s a community. Some are there by circumstance, having been encouraged to join by existing members in the pub one evening. Some are there for more poignant reasons, looking for new purpose having lost their wives and partners.

Others join for access to a social group. Peter Stewkesbury joined the choir in 2011, having not long moved to the Swansea area.

An Englishman, he knew as soon as he moved to South Wales, he simply had to join a male voice choir.

He finds solace in the choir and is often the butt of jokes, as you can imagine. “I’m really sorry you lost the game against 13 men, boys,” he quips in regard to that week's rugby game. The gents are used to it and take it in jest.

The future is an obvious problem for the choir. At 23 years old, I was the youngest there by quite some distance. Looking at the annual choir magazine that was given to me, there’s a noticeably weighty obituary section. Dewi Morgan, the publicity officer who showed me the vault, said that young people simply have too much to do to join a choir. This is realer than before in 2020, it’s very hard to believe that our social media generation will find the time, or even want to, have a sing twice a week with some old men in a chapel.

It’s a shame as there’s still life left in these old boys. They still sound as gorgeous as ever and can drink me under the table, which admittedly isn’t hard. Even after one rehearsal and a few pints afterwards, I can confirm that the notion of group singing enhancing one’s national and cultural identity is the bona fide truth. I felt more Welsh.

If the future is uncertain for choral singing, the future for Welsh music in general looks to be quite rosy. The Eisteddfod, where choirs of all ages still perform, and its cooler cousin Maes B, are still going strong (apart from this year of course). Welsh language music is enjoying a real moment, Welsh language music day – Dydd Miwsig Cymru – saw unprecedented success this February. Among music venue insecurity, there is optimism that a revitalised Cool Cymru could be on the horizon.

Herein lies the problem facing male voice choirs, they’re hardly up and coming. But congregational singing will never dissipate in Wales. We will still sing at the chapel, at the stadium and at the pub. Hell, even our accent makes a simple sentence sound like a song. Musicality will remain a distinctive trait of Welsh identity. As will a wicked sense of humour and a palpable sense of compassion, which Dunvant Male Voice choir have in droves.