Getting the band back together

Ten years ago, aged 16, my high school band recorded and released a metalcore EP to critical acclaim and a handful of downloads. After not playing together for almost a decade, I reached out to my ex-bandmates to attempt the reunion no one asked for

As a heavy music fan, there are fewer things that make you feel older than the ageing of influential albums in your life. In 2023, Linkin Park’s monumental Meteora turns 20—an album that dipped my toe into my future music taste. Even albums that refined my interest towards a more hardcore/metalcore palate in my teens, like Letlive’s The Blackest Beautiful, turn 10.

Another album turning 10 this year, arguably with significantly less of an impact on the hardcore genre, is my high school hardcore band’s self-released EP entitled The Origin. During my adolescence, being in a band and experiencing the cathartic nature of live hardcore shows was life changing. It’s no wonder that research suggests that making music as a group at this point of your life encourages teamwork, empathy and social bonding and makes a positive contribution to your subjective wellbeing.

Conversely, in my early twenties and at the height of the recent Covid 19 pandemic, I lived in fear of what the future of social interaction meant as a long term health sufferer, and my mental wellbeing suffered as a result. But just two years later, I spent my Saturday night dancing, singing and stage diving during a headline set from hardcore titans Turnstile at the sold-out Outbreak Festival and it killed my fears dead.

It also inspired me to reach out to my friends, most of which I hadn’t seen in years, and attempt to reform our band, the passion project of our teens that started my love for hardcore.

Although it was logistically doomed from the start, due partly to the reality of adulthood, my attempt to reunite my teenage band made me realise how much the experience sculpted my identity and brought me closer to my friends at a crucially formative time of my life.

The formation of the band

It’s best I start at how the band came to be. I spent the best part of my late teenage years a dedicated disciple of alternative music; in particular, hardcore punk. Every part of my being revolved around this world; my dress code included a mandatory band t-shirt at all times (excluding school uniform, of course); my weekends were spent slam-dancing on sticky club floors; even my moral code was informed by the anarchistic lyrics of bands like Refused and Trash Talk.

My interest in the genre inspired me to learn the drums, but there was still something missing when it came to fulfilling my true purpose within the hardcore community. Alternative music was the bond that held my tight-knit friendship group together, and the people who influenced us the most were all members of bands. The natural next step for me in the pursuit of purpose was starting a band.

In a Welsh language lesson, me and the band’s vocalist Jordan came up with an apt band name: Ancestors. From there, things went from strength to strength: we found a bass player, another school mate named Wez, and also two talented guitarists Nathan and Ed through mutual friends of friends.

Our combined love of hardcore meant we were all on the same page when it came to writing songs, and it wasn’t long before we had written and recorded our first (and only) EP ‘The Origin’ in 2013, which we fully funded ourselves. Everything after that made us feel like we were naturally heading to the top. We managed to pull off a sold-out EP release show in Fuel Rock Club, Cardiff and sell all the merch we had printed.

The band garnered the interest of a locally renowned artist and event management collective called Imperial Music, who agreed to add us to their roster. When this opened the door to playing shows with international inspirations like hardcore heavyweights Biohazard and melodic-hardcore titans Being As An Ocean, it felt like the dream was starting to truly become a reality. But there were also other (inevitable) forces in motion...

As we matured (to use the term lightly) into young men, the reality of adulthood began to creep its way into the forefront of our lives. Shows we were booked onto increasingly had to be cancelled due to newfound responsibilities. Practice sessions were rearranged, songs in the process of being written were shelved into Dropbox folders never to be opened again. University was the final nail in the coffin. The band was geographically stretched to its limit. In the band’s Facebook group chat, we solemnly came to a sobering and mutual conclusion: the dream was over.

The band officially ended in 2015. A final show was scheduled for early 2016, but never came to fruition. I was in my first year of university, and no longer a big fish in the small pond of the South Wales valleys, so to speak.

Just like that, life moved on as though dreams of touring the world were never even imagined in the first place. Some of us got jobs, some studied. We all paid our bills and grew into our twenties, focusing on the day-to-day rather than the glamorous prospect of a famous future.

Then, on a bitter January afternoon earlier this year, a Facebook message humbled me, sending me straight back to my 16-year-old mindset. “The Origin EP turns 10 years old this year,” my lifelong friend and ex-bandmate Jordan informed me.

The revival?

Instantly after receiving the message, I was teleported back to the EP’s release. At the same time my mind hypothetically filled in the blanks of the past 10 years as though the band had never split.

We never travelled for university, but instead travelled the US, sleeping in a tiny van and living off burgers recommended by local hardcore fans.

We had no degrees under our belts, but instead a number of critically acclaimed albums, loved by the music communities we happily served, particularly Australians.

Maybe, just maybe, we played the biggest ever Outbreak Festival in Manchester with Turnstile last year.

A cacophony of “what if” scenarios flooded my mind, until they merged into one overwhelming, intrusive rose-tinted suggestion: what if I got the band back together? The feeling matched that of the desire to form the band in the first place, tinged with aspiration and a missing sense of fulfilment. These feelings diminished shortly after messaging the unused band group chat to float the idea.

First to message back was rhythm guitarist Ed, who’s situation was now less geographically viable than when we all left for uni.

“I probably won’t be able to get over to Wales to jam as I moved to Scotland last year!” he informed us.

Ed didn’t take his guitars with him, and now spends most of his time as a conservationist, helping people take action for nature and their communities; a profession which (arguably) provides oneself with a lot more purpose than being in a hardcore band.

I began to think the prospect of reviving our teenage-hood band may not be enough to sway him into picking back up the guitar.

Next to message was lead guitarist Nathan, who had recently graduated after 7 years of studying medicine. He was understandably very busy, and on top of that had sold the majority of his guitars and music gear. Slowly but surely, the excitement surrounding the possibility of reviving the band felt like a distant dream.

My mood was slightly perked by a positive reply from Wez, the ex-bass player. He was up for the reunion, and was even still active in a few bands himself playing a number of different instruments.

As was our vocalist Jordan, who had been waiting for a message like this since the band had disbanded. My hope was somewhat restored, although it was evident there was some work to be done.

Thanks to the unstoppable passing of time, it seemed obvious that Ancestors wouldn’t return in the same form as days gone. But a benefit of the passing of time is the development of a number of technologies, particularly those that connect people who are widely spread geographically. Inspired by a number of musicians' innovation across multiple Covid lockdowns, including a magnificent and revolutionary live stream by Code Orange, I instead suggested a proposed reunion via Zoom. The boys were intrigued.

A virtual reunion

I scheduled the Zoom call for half past six on a Friday evening, the only time the majority of the band could fit it into their busy schedules. I quickly swigged a beer I had cracked open; I was quite nervous to talk to people I’d been so bonded to in the past, but since lost touch.

As seven o’clock approached with no reply from any of the boys, I started to feel defeated. The reality of adulthood had destroyed my teenage dreams of becoming a rockstar, and in turn ruined any chance of any form of band reunion as well. Then, akin to the swell of excitement before a band comes on stage at a gig, my pessimism was flushed away by a thick, Welsh-accented: “S’appening boys?” from my hardcore comrades.

It wasn’t long before we were all looking back with rose-tinted glasses, reminiscing a period of our lives that shaped our individual identities.

Conversation quickly turned to a show we played with Hundredth, Being As An Ocean and Black Tongue, three massive inspirations for us all at the time. “That show was the best show ever!” lead guitarist Nathan exclaimed.

“I'd already booked my ticket to that show, and then two weeks later we were on the bill. I remember being an 18 year old kid, and thinking: fuck me, this is the coolest thing ever!”

Wez, the band’s bassist, fondly remembers the band being pivotal in helping him realise his love for playing music, which he still does to this day.

“It made me a better musician on several instruments,” Wez admitted.

“I would never have performed live if it wasn’t for the band. It made me confident enough to realise my talent for rapping too.”

Conversation moved to the period after the band.

Ed, who joined the band later than the rest of us, confessed that he stopped playing musical instruments because he saw no purpose in it anymore.

“I wasn't in a band, there was no point to it,” he admits. “Gigging and writing was the whole reason [for playing] for me.”

As well as unlocking our creativity and giving us a sense of purpose, the Zoom call made me realise how pivotal the band was in improving and shaping us all as human beings.

“It just gave me a feeling of self-importance,” vocalist Jordan recalled. “For years and years and years, I just didn't feel that.”

Even though the Zoom call had reawakened the brotherly bond we’d built in our adolescence, it was obvious that performing together again was far from possible.

Though I was disappointed, it was enlightening to hear how much being in a band positively influenced the rest of the guys, as well as rediscovering the influence it had on myself too.

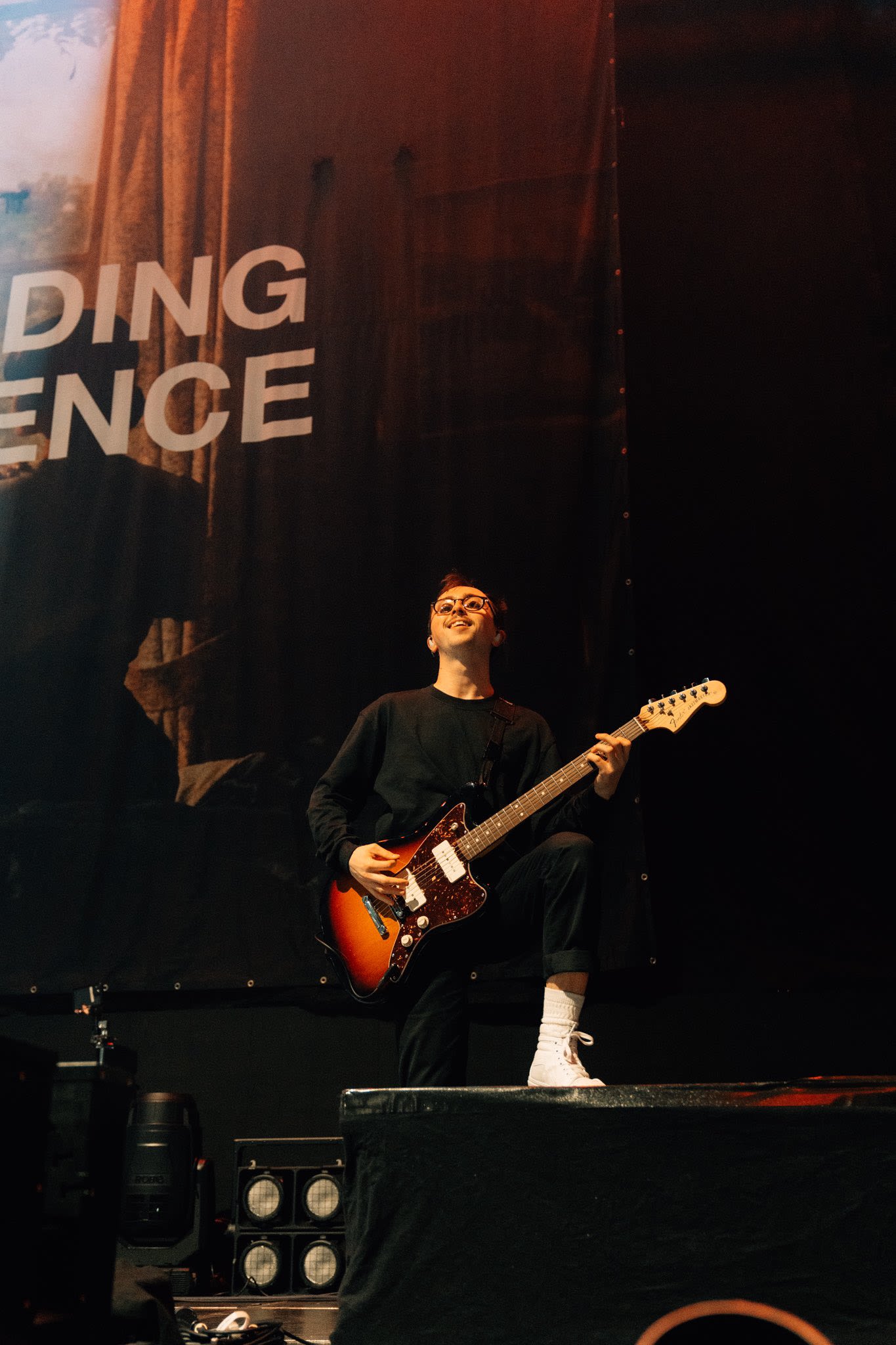

Ancestors never made it. But speaking to Scott Carey, guitarist in the band Holding Absence, it’s obvious the positive effects of being a band in your teens carry through even when you have made it. Scott was in his first band at 15 with people he still performs with to this day. “There was no judging or pressure in our small friendship group, we all loved hanging out and working towards our shared goal of becoming professional musicians,” he said.

Now, Holding Absence have toured the US, Australia and Europe and played massive UK festivals like Download and Reading & Leeds. “As we’ve grown as a band, we’ve expanded our little family worldwide,” Scott told me. “The sense of community we gain from this is something we all cherish deeply.”

The experience of attempting to reunite my own band made me realise: the positive influences of belonging, community and bonding that playing music with your friends in your teens offer are universal.

I’m eternally grateful I was able to experience positive male bonding at such an important stage of my own social development.

In today’s polarised social media communities, with influencers like Andrew Tate promoting misogynistic outlooks to teenagers looking to find belonging, I think that music as a mode of social bonding holds even more gravity.