I used an Afterlife bench to talk to strangers about grief for a month

Netflix placed 25 benches around the country inspired by Ricky Gervais’s hit series, but can they really open up conversations about death?

Anyone who is a fan of Afterlife knows the importance of a humble park bench for Ricky Gervais’s character Tony and his dog, Brady.

For me, the series demonstrated the reality of grief and the difficulty of finding hope after. Depicting the heart-breaking and yet humorous concept that is life.

My father passed away in a car crash when I was 15. Although I have processed the grief, speaking to other people, particularly strangers, is still hard.

When I heard Afterlife had teamed up with charity Campaign Against Living Miserably to plant 25 benches around the UK to encourage people to talk about grief, I was equally delighted and doubtful. Although the intent was clear, I’m always sceptical of whether the money put towards initiatives like this would be better spent on the crippled mental health services in the UK.

So, I decided to put it to the test.

Day one: 'I feel like I've been stood up on an imaginary date'

As I sit on a lone bench in Victoria Park, Cardiff, on a Sunday afternoon, I feel more alone than ever. The bench is damp, and the only thing keeping me warm is a cardboard cup of coffee between my hands. In front of me, a group of boys are playing football, and I sit here, their singular spectator.

As families, dog walkers and runners go by, I am becoming less optimistic that the quote indented on the bench is fulfilling its intended purpose.

I feel like I have been stood up by an imaginary date. As I feel the words ‘hope is everything’ at the bottom of my spine, I begin thinking that I’ll need an abundance of hope to get someone to sit here with me and talk about grief. At least in Afterlife, Tony had a dog.

After twenty minutes, I feel less embarrassed and decide to embrace the role of the crazy woman sitting on the bench alone. If a stranger won’t sit here and talk to me, I guess I’ll have to talk to myself.

My dad passed away when I was 15, and although there is not a day that goes by where I don’t think about him, there also isn’t a day where I actively choose to think about him.

After remembering the reason behind the bench, I begin thinking of my dad. I wonder what he would have thought of me, sat here alone on a Sunday afternoon.

We never went to parks. I grew up in the middle of nowhere and was always surrounded by greenery. So, I couldn’t really picture him sitting here with me.

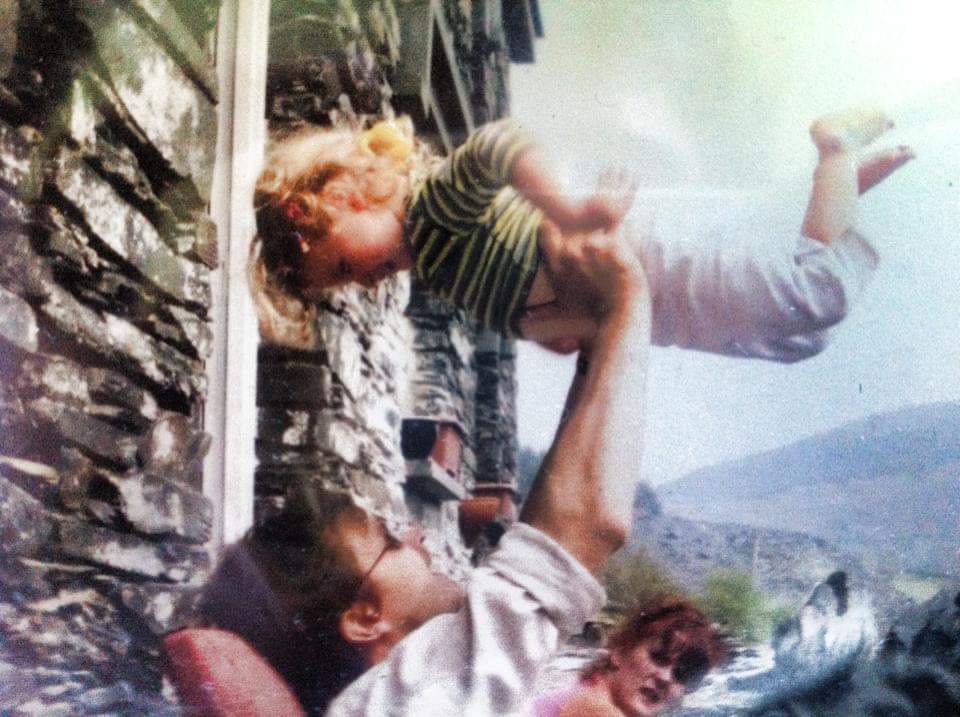

However, a few dads are pushing their children on bikes, putting them on their shoulders and swinging them around as they scream with laughter. I begin reminiscing about my dad chasing me around scrap yards, using broken washing machines as climbing frames.

Although my aim was to find someone to talk to about grief, sitting here and talking to myself feels like a positive step for the first time.

Method in the madness

After my first encounter with the bench, it felt good to take control of my thoughts. Of course, there are times when I will remember my dad randomly. But sitting on a bench intentionally thinking about him didn’t feel as painful. Instead, I could think of happy memories and dedicate a moment to him.

Along with the inscribed quote, the bench features a QR code to the Campaign Against Living Miserably website. I usually stay away from online resources on how to cope with grief. They tend to be filled with clichés and quotes telling you to stay strong. But after opening the website, I felt relieved as I read, ‘It’s common to hear them saying ‘time is a healer’ or words to that effect, but grief isn’t something you ‘get through’. It can resurface years after a loss and can feel just as intense’.

One of the aspects of Tony’s grieving process on Afterlife that I relate to the most is his suicidal thoughts.

Although the quote ‘hope is everything’ may seem frivolous, anyone who has experienced grief will know how difficult it is to find hope in life after death.

In the years after my dad passed away, I constantly asked myself, ‘what is the point’. Whether it was completing my degree, making new friends, or even eating dinner. I repeatedly wondered, ‘what is the point if we all die in the end?’. Perhaps it was how my dad died, but the swinging back and forth from ‘do what I want when I want because life’s too short’ and ‘what’s the point of anything if we could die tomorrow’ left me seasick for much of my teens and early adulthood.

However, my friends would later become the turning point in my bereavement as we would share open conversations about grief and our loved ones. Without them, I would have still found it difficult to talk about my dad, even with those close to me.

According to research, it is not uncommon for bereaved adolescents to find it difficult to confide in others. A 2018 study by the University of New South Wales found ‘bereaved adolescents were very selective and shared their experiences with a few specific confidants only’. Not only this, but they also had high levels of self-reliance and wanted to manage themselves.

Amy Dryburgh, a mental health support worker, is currently fundraising money to supply primary schools in west Wales with ‘buddy benches’, a bench used to encourage discussions around mental health from a young age.

“The benches allow for these conversations to happen in a natural way. Conversations around mental health can be quite scary if done so in a clinical setting. These benches are a safe space for individuals to have these conversations with those who may be experiencing similar thoughts and feelings,” she said.

Day two: 'I'm beginning to feel like their mascot'

I’ve returned to the bench with the addition of a scarf and gloves, less intimidated but still fearful of the emotions that may arise.

Unfortunately, the group of boys playing football have also returned. At this point, I’m beginning to feel like their mascot.

Five minutes in, I start preparing to talk to myself again when a ball slowly makes its way towards me.

I start panicking.

As if sitting on this bench a week later, watching the same group of boys play football, wasn’t embarrassing enough. Now, I would have to kick a ball back to them, most probably in the wrong direction.

Luckily, one of the members gets here before the ball, and I make myself known and say hi.

We do the usual small talk about the weather, and he asks me what I’m doing, and I tell him about my experiment.

He says he had no idea that the bench was an extension of his favourite Netflix series.

Somehow, I manage to convince him to sit and talk to me about my dad as he reveals he had recently lost his grandad, who was the ‘family icon’.

We talk for ten minutes about grief and Afterlife. He tells me the yoga scene had him in stitches, knowing it was exactly how his grandad would have reacted.

When we finish talking, he runs back to his friends, wishing me all the best and reminding me to take care of myself.

Although the conversation was short, opening up about something we may not have shared with friends reminds me I am not alone in my experiences.

I leave feeling slightly exposed but excited for my next trip to the bench.

Day three: 'I was there to help someone grieve a recent loss'

As I walk to the bench for the third time, I notice someone sitting in my spot, which is the first time I've seen someone other than myself sitting on the bench.

I ask if I can sit next to him, hoping he'll say yes otherwise, I've just wasted a 40-minute walk through a hungover Cardiff after their six nations game against Italy.

He politely agrees, and I sit close to the edge to not disturb his personal space.

For a few minutes, we sit in silence. I didn't want to interrogate him as to why he is here as soon as I sat down, in fear I might scare him off.

Luckily, just as things were about to get a little too awkward, a big ball of golden fluff comes running up to us, begging for some attention.

His owner swiftly grabs the over-excited dog and apologises for his abrupt introduction.

The man sitting next to me replies, "don't worry, I'm used to it."

Great, there's a conversation opener. I wait until the dog owner leaves to ask him about his own dog.

"She was a black lab. Susie was her name."

I do the usual aw's and then proceed to tell him about my old dog called Guinness, who passed away not long after my dad.

As I do this, he becomes more comfortable with me. He reveals he had put his dog down on Friday, and this was her favourite park as she could go and chase other dogs' toys on the football field opposite the bench.

"My dog was actually older than my son. She really felt like part of the family."

We joked about how a dog's passing may seem trivial to some, but it can feel like you've lost a limb when they have been in your life for such a long time.

As I left, I realised I hadn't spoken about my dad, but that wasn't the point. I was there to help someone grieving a recent loss and remind them that how they are feeling is valid.

Day four: 'We didn't talk about our loved ones, just our lives after'

My final experience on the bench was bittersweet. Within minutes of sitting down, a woman and her son sat next to me. Luckily, he broke the ice immediately as he ran around us, showing off his new light-up shoes.

As this was my final time, I decide to go head first and tell her what I’m doing on the bench. She seems taken aback, responding, “I didn’t realise it was a bench dedicated for that, and I only thought it was new because it didn’t have mould and bird poo.”

Hesitantly, she explains that her sister died when she was 15, and her family hasn’t recovered since: “When I was pregnant, all I wanted was for her to be beside me and help me through it. It’s the big life events where you really feel there is a missing piece.”

This was something I had struggled with too. My dad passed away a few weeks before I got my first set of GCSE results, and since then, major life events have been tainted knowing he’s not there.

“Although every day gets easier, grieving someone in early adulthood can be really difficult.” She said quite unconvincingly.

We spent the rest of our time together talking about grief and our experiences with it, especially in school. Unlike the previous times on the bench, this time, we didn’t talk about our loved ones, just our lives after.

Soon enough, her son was hungry, and they left to go home.

I stayed on the bench, processing the conversations I had over the month, feeling a little deflated.

After using the bench for a month, I feel more comfortable talking to strangers about death and my own bereavement. Each person I encountered dealt with loss of some kind, which affected them all differently. Not only did this make me feel less alone, but I enjoyed reminiscing about my dad as well as getting to know other people’s loved ones.

Although I was sceptical, the Afterlife bench truly is a simple yet effective way of encouraging people to talk about grief. With schemes such as the Buddy Benches, I hope young people will feel more comfortable having these difficult conversations and eventually, death will no longer be a taboo topic.

Of course, it was an emotional experience, but ultimately, it was incredibly uplifting.