'The most worthwhile thing I have ever done'

At 22 years old, Natalie Wainwright became one of the youngest people in the country to be a foster carer

After months of intense assessment, Natalie Wainwright sat before a panel of eight people, anxiously waiting to hear the unanimous “yes” she’d been praying for.

Despite her growing anticipation, nothing could have prepared her for the paradoxical love and heartbreak that lay before her.

It felt like everything was building up to that day, she said softly, recalling the moment that would come to mark her life in more ways than one.

The process leading up to this point had pulled Natalie in many directions, often causing her to lose her footing. At times, it was tiresome and consuming. Many wouldn’t understand, others would raise eyebrows, and some would say she was giving up too much.

She had come a long way, but her story was only just beginning.

At 22 years old, Natalie, born and raised in the small seaside town of Worthing, West Sussex, became one of the youngest people in the UK to be a foster carer.

For those who know her, the trajectory she has chosen for her life, though wildly unconventional, is no surprise at all. Tender of heart and with a disposition speaking of a wisdom well beyond her years, it’s clear to see she was made for motherhood. Somehow, it’s in her nature - perhaps the warmth of her voice gives her away.

Tender of heart and with a disposition speaking of a wisdom well beyond her years, she was made for motherhood. Somehow, it’s in her nature - perhaps the warmth of her voice gives her away.

“I came out of the panel meeting that day, and almost within a minute, I was asked to take care of my first foster child,” Natalie began, thinking back to the moment that stole her breath.

“She was a little girl of three years old, and sadly, her mum had abandoned her and was missing,” she explained.

As a single carer, Natalie would be able to give her the one-to-one support she needed.

The following week, with a small bag of belongings under her arm, the little girl arrived at the door of Natalie’s apartment. She unpacked her few things and settled herself down in her new bedroom which was carefully prepared for her.

The connection was instant, Natalie recalled. “She came and sat on my lap and we played in the sandpit together,” she said. Smiling, Natalie added, "Just like that, she became my foster daughter," and for the next 11 months, their bond was inseperable.

"She was a little girl of three years old, and sadly, her mum had abandoned her and was missing"

With a background in teaching and having grown up with foster brothers and sisters of her own, Natalie didn’t begin her journey unequipped. Her parents, Tracey and Paul Wainwright have now been long-term foster parents for more than 15 years.

“We’re passionate about helping vulnerable children, so having a busy house is just how we like it,” Tracey explained in an interview for West Sussex County Council.

It’s a fantastic sense of fulfilment seeing children who need a second chance helped onto a better pathway, Paul added.

Having Tracey and Paul’s support throughout the fostering application process was a close comfort and encouragement to Natalie. With years of first-hand experience of the realities of care, she knew she could turn to them for advice whenever she needed someone to lean on.

Following in the footsteps of her parents as they opened up the doors of their home to multiple children at a time, Natalie always knew that foster care would be part of her future. Being 10 years old when she was first introduced to her foster siblings, she became aware of the stories and struggles faced by children in the care system at an early age. Their experiences, often characterised by confusion, pain, rejection and neglect, were enough to both break her heart and move her to action.

“I saw the difference fostering made for my parents,” Natalie said. “I looked up to them and watched how that kind of love changed them over time,” she remembered fondly.

In 2016, Natalie graduated from Brighton University with a degree in primary education. After working for a year as a teacher and attaining her NQT, she started a new role at a local nursery in Sussex as an early year’s practitioner.

Looking back on the unfolding chapters of her story, Natalie spoke of her time visiting rural East Africa during her summer breaks. For her, these experiences stand out as significant milestones on the road to becoming who she is today.

In 2015, she travelled to a village in Rukungiri, Uganda where she volunteered with relief and development organisation, Tearfund. The following August, she packed her bags and set off to Nakuru, Kenya where she worked closely with local non-profit, Sure 24, which provides care and education for over 300 vulnerable children in the community.

Hearing the stories of the children and their families who had experienced deep trauma as a result of abandonment, poverty and illness, an urgency to make a change stirred within her again.

Though separated by continent, culture and creed, she saw a common running thread.

She found the challenges faced by those she met overseas in many ways, naturally resembled the trauma experienced by the children she knew in the UK care system.

While different in many ways, they both shared in this injustice.

While continuing to actively support the positive work taking place in Rukungiri and Nakuru, Natalie’s mind kept coming back to the vulnerable people in her own community.

Though separated by continent, she saw a common running thread. An urgency to make a change stirred within her again.

It felt like a scary path to walk down, but she knew what she needed to do next.

And this time, she knew she wouldn’t need to travel further than her hometown.

Refusing to ignore the pull of her heart towards foster care, she started making enquiries about the process in 2017.

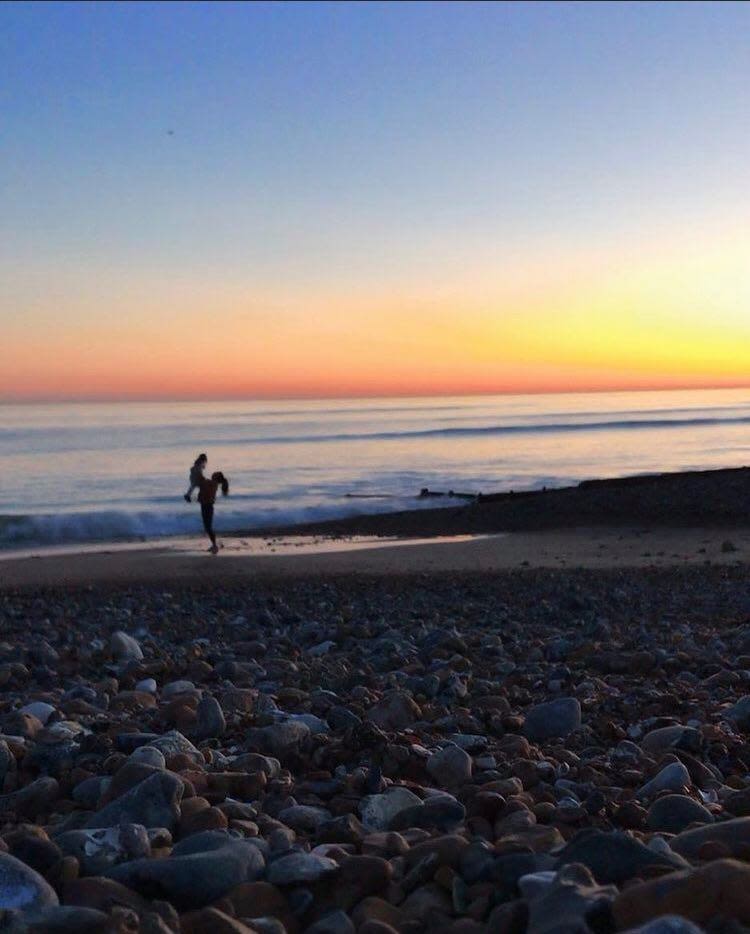

The seaside of West Sussex, England, Natalie's home county

The seaside of West Sussex, England, Natalie's home county

Research by the Fostering Network suggests over 65,000 children live with almost 55,000 foster families across the UK each day. This is nearly 80% of the 83,000 children in care away from home on any one day in the UK.

With around 30,000 more children coming into care over the course of 12 months and similar numbers leaving the care system to return home, move in with another family member, live with new adoptive families or become subject to special guardianship, thousands of new foster families are needed each year.

In the midst of the pandemic and as the number of children requiring care in the UK began to surge, British non-profit, Barnardo’s, declared a state of emergency in June 2020. According to the charity, the number of children needing foster care rose by 44% during the coronavirus pandemic. At the same time, the number of people looking to become foster parents plummeted by nearly half compared to the same period last year.

The charity believes that lockdown has increased pressure on vulnerable families with deepening poverty, job losses and worsening mental health, unfortunately all leading to family breakdown. In an interview for the Guardian, Barnardo’s chief executive, Javed Khan explained, “The coronavirus pandemic has hit vulnerable families the hardest, with many reaching crisis point.” As a result, children have been in lockdown in homes where domestic and sexual abuse are taking place.

In a bid to inspire more people to become foster parents, Khan added, “Today, there are hundreds of children who have been referred to Barnardo’s and are waiting to be placed with a foster family. If you’re over 21, have a spare room and the time and commitment to support a child in need, please do consider getting in touch today.”

"Today, there are hundreds of children waiting to be placed with a foster family"

Though the average age of a foster carer in the UK is between 45 to 54, during the application process, Natalie explained she never experienced any apprehension from social services because of her age.

“They were so much more interested in my reasons for wanting to foster, so it was really encouraging to me that they didn’t see my age as a barrier. They were really supportive” she said.

Having recently moved out of her family home at the end of her first year of teaching, Natalie hadn’t been living alone for long. She continued, “I personally had a lot of fear about whether I could do it and whether I could deal with the challenges that would come my way. But I was really honest with the social worker about my worries, and she helped me work through them,” she said confidently.

Despite the commonly asked questions about her plans from people around her, Natalie knew it was time to throw herself in the deep end. With worries that she was “putting limitations on herself” or “giving up her social life too soon”, she decided to put aside the opinions of others.

She added, “I realised I could give power to my fears, or I could rise up and go ahead. What other people thought didn’t matter to me anymore.”

“I feel quite passionate about young people fostering. It’s not something that happens every day, but I think young people and the millennial generation have so much to give,” Natalie explained.

While her lifestyle doesn’t reflect that of a typical girl in her age bracket, she believes foster carers do not need to look “one particular way”, be part of a conventional family, or even have a partner.

She affirmed, whatever your stage of life looks like, you can do it.

Now 25 years old, Natalie has been a foster mother to three different children in just under three years.

“At the moment, my day usually starts with singing,” Natalie laughed.

Currently caring for another little girl of three years old, Natalie shares her daily routine as a foster parent in the pandemic.

“I know when she’s awake in the morning because I can hear her signing her heart out and playing the guitar from across the apartment. She’s my daily wake up call,” she joked.

After having breakfast together, Natalie helps her get dressed for the day.

Working part-time at a local nursery, her foster daughter usually accompanies her to work where she can play in the garden, meet other children and climb the trees. Other days, they’ll go for walks together, head to the seaside, or spend the afternoon collecting pinecones from the forest.

Recalling the highs and lows of motherhood so far, Natalie spoke slowly and thoughtfully, her voice growing more earnest as she traced back the memories.

With the inevitable sting of goodbye ever lingering in the back of her mind, each joyful moment shared with her foster children leaves her with a bittersweet ache.

“The goodbyes don’t get easier with time,” she revealed.

“I love looking after these children, championing them and helping them belong. But at the end of it, there’s always that goodbye. There’s no way around it,” she said.

“I love looking after these children, championing them and helping them belong."

In her grief, Natalie has learnt to surrender to the sadness she feels when the time comes for her foster children to move on.

Recognising the importance of giving herself space to heal, she remembers the victories and wins she saw the children overcome while in her care.

Despite the odds that are stacked against them and the difficult start they’ve had in life, proudly watching her foster children grow up is one of Natalie’s greatest privileges.

For her, celebrating them is her richest reward.

Looking forward with bright eyes, she hopes she’ll still be fostering when she’s 50 years old. Though she may take a break when she adopts or has children of her own one day, she knows fostering will continue to be part of her story for decades to come.

“Even when it hurts to say goodbye, I remember why I’m here. The unconditional love I feel makes the heartbreak worth it every time - It’s the most worthwhile thing I have ever done.”